GossipLog - reliable causal broadcast for libp2p

Joel Gustafson / Posts / 2024-09-30

In the last post, we introduced the causal log as a general-purpose foundation for eventually-consistent replicated applications. The promise is essentially that a single causal log can abstract away the practical "hard parts" of decentralized CRDTs: networking, syncing, access control, and so on.

GossipLog is a self-certifying replicated causal log implementation, with storage backends for SQLite, IndexedDB, and Postgres. It uses libp2p for peer-to-peer networking, and achieves reliable causal broadcast using a novel merkle sync protocol.

#Table of Contents

#Data structures

#Causally-ordered message IDs

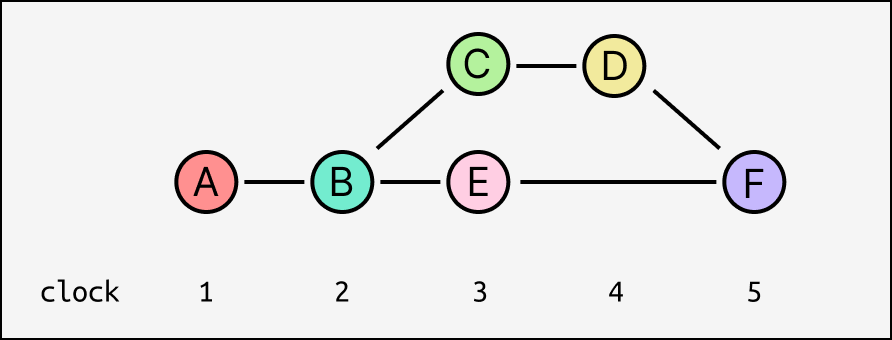

When working with causal logs, it's extremely useful to have IDs for the messages that sort according to causal order. A natural way to do this is to introduce a logical clock for the log, where each message has a clock value equal to one more than the max clock value of its parents (or 1 for initial messages with no parents). This value is equivalent to the maximum depth of the message's ancestor graph.

Concurrent messages might have the same clock value, but every ancestor of a message is guaranteed to have a smaller clock value, and every descendant is guaranteed to have a larger clock value.

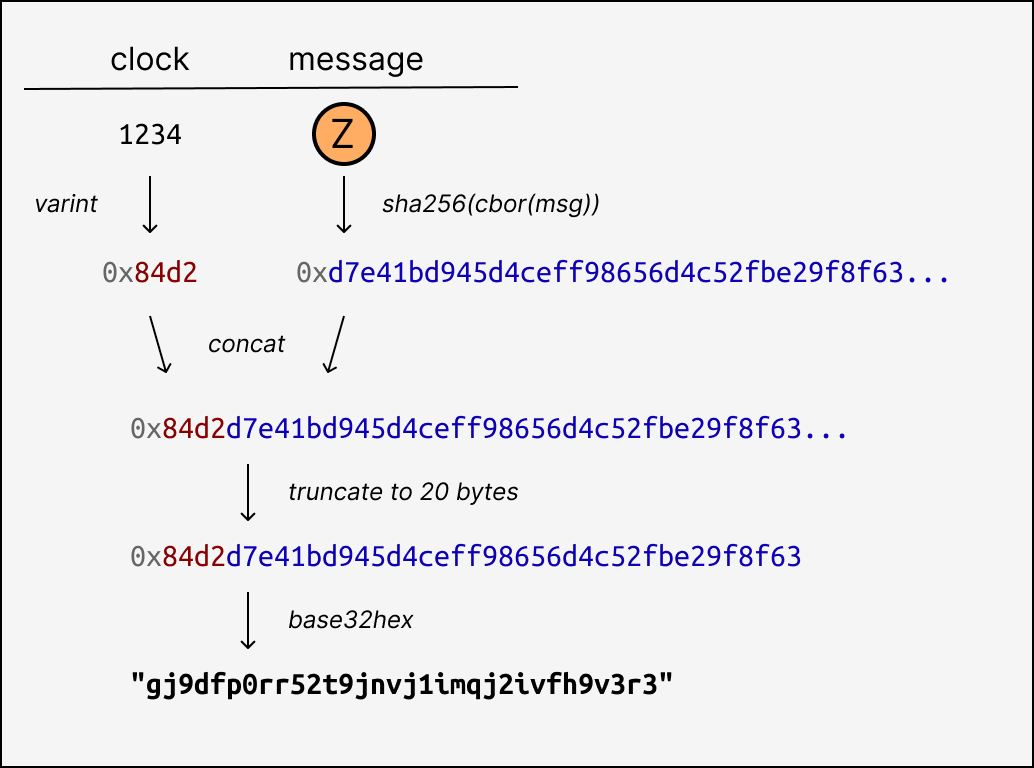

GossipLog uses a message ID format that begins with the clock value as a variable-length integer using an order-preserving prefix-free encoding. This is concatenated with the sha256 hash of the dag-cbor-encoded message, truncated to 20 bytes total, and encoded to a string using base32hex. This produces unique 32-character alphanumeric identifiers that follow causal order: if A is an ancestor of B, then id(A) < id(B).

This makes implementing eventually-consistent last-writer-wins registers especially simple, since the message IDs themselves are sufficient to determine effect precedence.

#Messages

Log entries consist of a Message and a Signature.

type Message<Payload> = {

topic: string

clock: number

parents: string[]

payload: Payload

}Messages have an arbitrary IPLD payload, and an array of parent message ids. The topic is a globally unique name for the entire log, which replicas use to locate each other. All messages in the log have the same topic.

#Signatures

GossipLog is designed for self-certifying applications. This means every message in the log is signed, and the signature is stored and replicated as part of the log entry.

type Signature = {

codec: string // "dag-cbor" | "dag-json"

publicKey: string // did:key URI

signature: Uint8Array

}The signature mechanism is generic and self-describing. Each Signature object records the codec used to serialize the message to bytes for signing, the public key as a did:key URI, which also identifies the specific signature scheme, and the bytes of the signature itself.

#Network protocol

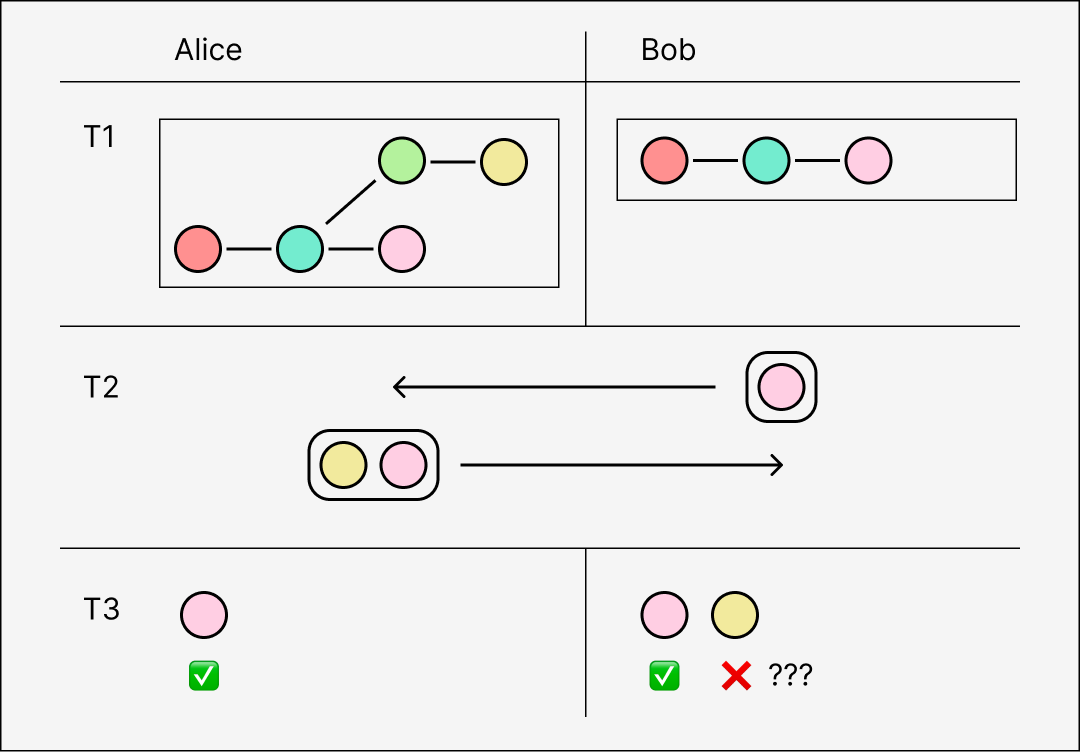

When Alice appends a new message, she needs to broadcast it to the rest of the network. If the message somehow fails to reach Bob, that's bad for the obvious reason (he is out of sync with Alice), but it's also bad because it means Bob will be unable to apply subsequent messages published by Alice even if he receives them.

A causal log promises that messages will be applied in causal order, which many useful kinds of CRDTs require. Bob can't apply a message until he has applied all of its transitive ancestors; "orphan" messages with missing parents must be discarded or queued until their dependencies are met.

What peers need is reliable causal broadcast - a way to guarantee delivery of messages, in causal order, to all other peers. But no such network primitive exists. Just like TCP, we have to build a reliable protocol out of fundamentally unreliable components. GossipLog uses two complementary protocols: pubsub and merkle sync.

#Pubsub

GossipLog's namesake is gossipsub, a decentralized pubsub protocol for libp2p developed by Protocol Labs. The gossipsub protocol was designed to support large networks with high message throughput, and to be as resilient as possible to spam, Sybil attacks, eclipse attacks, and other adversarial behavior. There's a paper on arXiv with large-scale attack testing results, and it was adopted as the broadcast protocol for Ethereum's Beacon network.

There is perennial confusion among libp2p users about what gossipsub does and doesn't do. It specifically doesn't provide peer discovery: it assumes all peers are already connected and that new peers have an existing way of finding and maintaining a balanced mesh of connections to other peers in the network. We will discuss peer discovery later.

Within an existing well-connected network, gossipsub maintains an overlay mesh for each topic. The overlay mesh is a subgraph of the physical connection graph, meaning a peer's gossipsub service may or may not choose to add physical connections to its local mesh for a topic (called "grafting") and may choose to remove an edge from the local mesh without closing the underlying connection (called "pruning"). This sparse overlay mesh, along with other optimizations like distinct push-vs-pull modes, are what let gossipsub scale to many peers with high throughput without flooding the network.

GossipSub gives us low-latency broadcast to open networks with good-enough attack resiliency. In the ideal case, this would be sufficient for publishing new causal log messages. But GossipSub is best-effort and ephemeral. It doesn't give us any kind of delivery guarantees, persistence, or syncing. Messages might be dropped or re-ordered, and even if they aren't, we still have to deal with the case of new peers coming online, or peers dropping off and coming back later. Maybe Bob lost his internet connection for a minute, during which he appended a dozen important messages to his local log. How does the rest of the network find out?

#Merkle sync

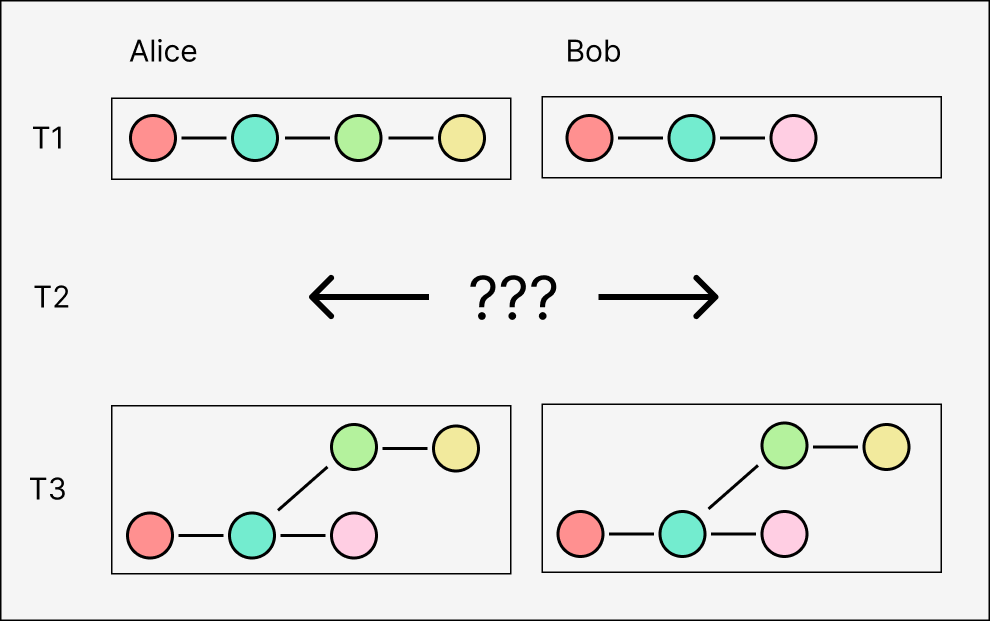

Whenever two peers connect to each other, a sensible first step is figure out if either has messages the other is missing, and to acquire those messages from each other.

One way of doing this is to have peers exchange their current set of branch "heads" (messages with no descendants), which uniquely identify the entire set of messages in their respective logs. If one peer is missing any of the ids in the other's set of heads, they know they're missing one or more messages that the other peer has.

What to do next is a more difficult question. We could have peers request missing messages individually from each other, in a step-by-step graph traversal. But this yields messages in reverse causal order, from most to least recent - the opposite of what we want! In the worst case, a new peer joining the network with an empty log would have to request every message from another peer's entire log one-by-one from head to tail, and buffer them all before applying them last-in-first-out. This also opens up a new attack vector in which a malicious peer claims to have an infinite number of nonexistent messages, and overflows the buffer of peers trying to sync with it.

We want our log to work well even with millions of entries, and for syncing to be as fast as possible even between peers that have long divergent branches. What we really want is a sync algorithm that efficiently yields missing messages in forward causal order, so that they can be applied (and validated) as they are received. This is GossipLog's second component: merkle sync.

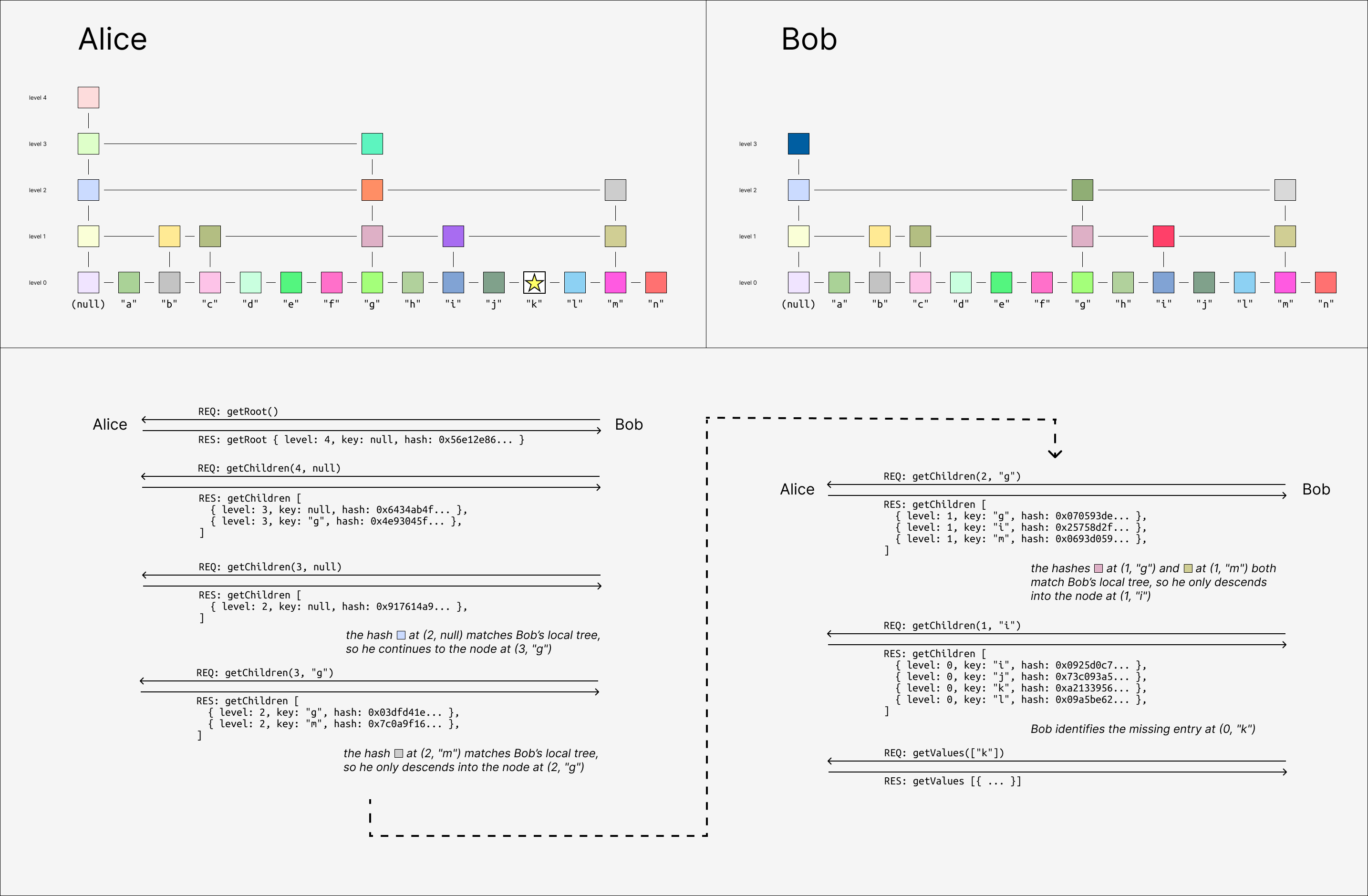

In addition to storing message contents in a SQLite database, GossipLog maintains a prolly tree over the message IDs. A prolly tree is essentially a pseudorandom merkle skip list, and it can be used like a syncable key/value index. Two peers with prolly trees over their message IDs can efficiently iterate over the diff of their entries, regardless of how conflicts are distributed throughout the leaves. Crucially, the syncing process yield differences strictly in lexicographic order by key.

See this previous post for an introduction to Prolly Trees and their implementation!

Prolly Trees are similar in principle to content-defined chunking, used in rsync since 1996. An important difference is that rsync can only be used in one direction - pulling in changes from a single source of truth - but merkle sync yields entry-wise diffs. This means Alice and Bob can each have many respective divergent branches and still sync with each other at the same time. Alice will yield the messages she's missing from Bob, skipping the messages she has but Bob doesn't; Bob will yield the messages he's missing from Alice, skipping the messages he has but Alice doesn't.

These are artificially tall trees - GossipLog uses an average fanout degree of 32 in production.

The merkle sync primitive is good because it is complete and stateless: it yields every missing message, in causal order, regardless of the ancestor graph topology, and doesn't require peers to know anything about each other beforehand. Syncs can even be aborted at any time by either party - e.g. for rate-limiting reasons on a high-traffic public peer - and will naturally resume from the same place if restarted.

The general problem of efficiently calculating set difference is called set reconciliation, and there are other similar data structures that can solve the same problem, like merkle search trees (MSTs), merkle tries, and range-based set reconciliation (RBSR). In general, prolly trees are simpler to implement than MSTs, aren't limited to fixed-sized keys like tries, and have comparable performance to RBSR.

#Reliable causal broadcast

We can now describe GossipLog's reliable broadcast implementation as the combination of three lower-level libp2p protocols:

- A push protocol, in which a peer proactively sends its heads (most recent concurrent branch ids) to another peer. This happens in two cases:

- Whenever a new connection is opened, both peers push their heads to the other, so that the recipient can initiate a merkle sync in response if necessary.

- Whenever a peer finishes an merkle sync during which it received one or more missing messages, it pushes its new heads to all of its peers, except for the sync source.

- A sync protocol, which one peer initiates with another. The initiator has a "client" role, making RPC requests for various merkle nodes in the server's prolly tree, although these are only roles and don't correspond to literal client/server runtime environments. Merkle syncs are initiated in two cases:

- When a peer receives an orphan message via gossipsub, it schedules a sync with the gossipsub message's "propagation source" (the direct peer that delivered the message on the last hop, not the original publisher).

- When a peer receives a push update with missing heads, it schedules a sync with the sender.

- The gossipsub service. Every peer subscribes to the log's topic, and publishes every append to it.

- Crucially, gossipsub has an async validation feature that exposes control over whether a message should be accepted and forwarded to the mesh peers, rejected and the propagation source penalized, or silently ignored.

- If a peer receives an orphan message via gossipsub, it instructs the gossipsub service to ignore the message, and schedules a merkle sync with the propagation source.

- Peers only forward messages along the gossipsub overlay mesh if they have all of the message's parents. This guarantees that the recipient of an orphan message can always attempt to recover both the message and its missing ancestors via merkle sync from a peer it is already connected to.

Of course, this can't guarantee delivery of every message to e.g. offline nodes. But altogether, GossipLog exhibits ideal practical behavior for a replicated causal log. New peers immediately sync upon first connection. New messages are delivered promptly to all peers that can accept them. Old messages quickly diffuse across the network via merkle sync and push updates.

#Peer Discovery

How peers get connected in the first place depends on the environment. GossipLog supports two different connection topologies:

#Browser-to-server hub-and-spoke

Browsers are the most common platform for modern applications, but their peer-to-peer networking capabilities are severely limited. Web apps can't open sockets directly, and are constrained to WebSockets, WebTransport, and WebRTC. WebRTC is notoriously complicated, prone to misconfiguration, doesn't work in all network conditions, and still needs access to third-party STUN/TURN servers to relay traffic if necessary. WebTransport still not available in all browsers. This only leaves WebSockets, which can only communicate with servers, and only over TLS.

Browser GossipLog peers can connect to a server peer over a WebSocket connection. This gives a hub-and-spoke connection topology with the server at the center, connected to many browser clients, syncing and propagating messages between them.

Here are some screen recordings of our network testing environment, which uses Docker compose and Puppeteer to orchestrate different topologies, streaming events and metrics to a D3 dashboard in real-time. Peers join the network after a random delay. The color of each peer is derived from the root merkle hash of the log, so nodes that are the same color have exactly the same log entries, and nodes of different colors are out of sync.

Above, we append random messages manually by clicking on nodes, and see that they instantly propagate to the rest of the network. As new clients join the network, they can tell from the server's initial push update that they're out-of-sync, and immediately start a merkle sync that yields all of the missing entries. This causes the "jump" to the current latest color right after they connect to the hub.

Below, all peers automatically append messages at random.

#Server-to-server p2p mesh

Browser support is nice, and hopefully the browser becomes a more viable platform for p2p apps in the future, but for now the real fun can only happen server-to-server.

A NodeJS GossipLog peer can connect directly to other servers, as well as accept connections from browser peers. It uses libp2p's kad-dht (Kademlia, a distributed hash table) module for peer discovery and connection management.

GossipLog doesn't actually need the DHT itself since it has nothing to store and look up, although the capability may be useful in the future. However, a large part of the DHT implementation is actually dedicated to maintaining a balanced connection topology. For DHT record look-ups to work efficiently, each peer in the network needs to have active connections to roughly equal-sized groups of peers in every order of magnitude ("k-bucket") of distance from themselves, for some triangle-inequality-respecting distance metric. Kademlia uses the XOR of the hash of peers' public keys for distance, which is unintuitive to visualize but works well in practice. The libp2p kad-dht service continuously queries its neighbors for information about other peers in desired k-buckets, and dials them when needed.

This all means that even for networks that don't need DHT provides and look-ups, using the DHT module is useful as a simple way for managing self-organizing p2p meshes. New peers can bootstrap into the network by connecting to any existing peer, and will quickly connect to a spare set of peers spanning the rest of the network.

Here's a network of 64 peers all bootstrapping to the same server (in black), and then organizing themselves using the DHT service.

Then we can watch gossipsub propagate of messages across the mesh in real-time!

Here, the black triangle decorations on the edges indicate inclusion in gossipsub's internal topic mesh. Only some connections are grafted into the topic mesh.

Another important aspect of syncing is when a new peer has messages that the rest of the network doesn't, such as a user interacting with an app while offline. When it first connects to another peer, it's not enough for that peer to sync the messages - the entire rest of the network must eventually receive them too!

Here, peers all join with a small number of unique local messages (see that the new peers are all different initial colors, unlike the previous examples). Once they connect, their local messages propagate through the network through alternating push and sync steps. This is slower than gossipsub, but still converges quickly.

#Conclusion

The goal of this post was to introduce causal logs as a useful primitive for building decentralized applications. We saw in the previous post that causal logs are found inside CRDT frameworks, but they're also useful outside those frameworks. Any application that uses pubsub might want reliable delivery to go with it, even if the messages aren't "CRDTs" per se. GossipLog can be used for broadcasting anything.

The uses of replicated causal logs also extend beyond classical CRDTs into a broader class of computations, limited only by a generalized constraint called confluence (or logical monotonicity). It's actually possible to use the log to replicate e.g. the bytecode of database transactions, as opposed to a fixed set of CRDT operations, so long as the effect of evaluating the bytecode satisfies eventual consistency. The typical framing of CRDTs doesn't actually do a good job of capturing the space of possibilities here.

Today, you can use GossipLog as a JavaScript library in the browser or NodeJS, and it's probably of particular interest if you're already using libp2p for a decentralized application. At Canvas, we're using GossipLog as the foundation of a new distributed state management framework - another layer of the stack which we'll cover in a future post.

#Further reading

- GossipLog on GitHub

- Keeping CALM: When Distributed Consistency is Easy

- Byzantine Eventual Consistency and the Fundamental Limits of Peer-to-Peer Databases

- Merkle Search Trees: Efficient State-Based CRDTs in Open Networks

- Merklizing the key/value store for fun and profit

- Range-Based Set Reconciliation

#Appendix

#Order-preserving variable-length integers

The standard variable-length integer format used in Protobuf, multiformats, etc encodes integers into sets of seven bits, using the first bit of each byte as a "continuation bit". This is efficient and simple to implement, but doesn't preseve sort order.

Instead of dividing up the encoded bits into sets of seven, we encode the integer into (big-endian) binary and prefix the result with the unary number of extra bytes needed to store it (not including the first byte). The binary value is then "right-aligned" within the final result buffer.

| input | input (binary) | output (binary) | output (hex) |

| ------- | -------------------------- | -------------------------- | ------------- |

| 0 | 00000000 | 00000000 | 0x00 |

| 1 | 00000001 | 00000001 | 0x01 |

| 2 | 00000002 | 00000010 | 0x02 |

| 127 | 01111111 | 01111111 | 0x7f |

| 128 | 10000000 | 10000000 10000000 | 0x8080 |

| 129 | 10000001 | 10000000 10000001 | 0x8081 |

| 255 | 11111111 | 10000000 11111111 | 0x80ff |

| 256 | 00000001 00000000 | 10000001 00000000 | 0x8100 |

| 1234 | 00000100 11010010 | 10000100 11010010 | 0x84d2 |

| 16383 | 00111111 11111111 | 10111111 11111111 | 0xbfff |

| 16384 | 01000000 00000000 | 11000000 01000000 00000000 | 0xc04000 |

| 87381 | 00000001 01010101 01010101 | 11000001 01010101 01010101 | 0xc15555 |

| 1398101 | 00010101 01010101 01010101 | 11010101 01010101 01010101 | 0xd55555 |This general format can encode integers of any size, but since JavaScript can only safely represent integers up to 2\^53-1, the unary prefix has a maximum length of ceil(53/8) = 7, and will always fit into the first byte.