Introduction to Causal Logs

Joel Gustafson / Posts / 2024-09-30

People use apps, apps use databases, and databases use logs. Logs are useful because they make distributed replication easy, and can be deterministically reduced, but they're inherently single-writer. All appends must go through a single point.

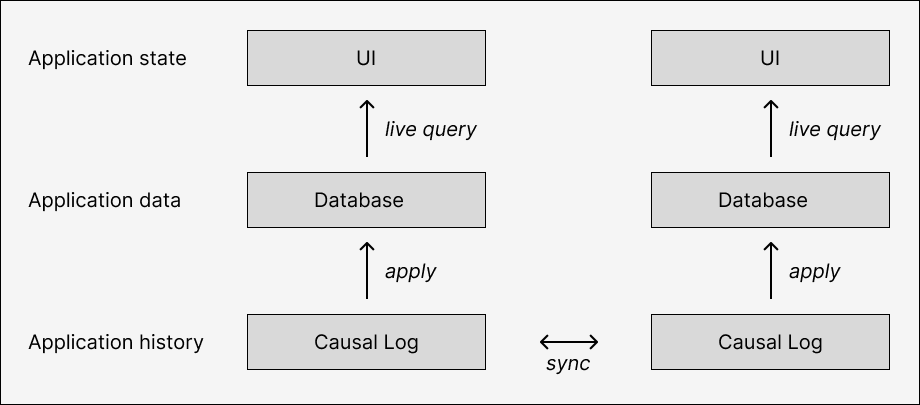

The log has a partially-ordered cousin, the causal log, that does natively support multiple concurrent writers. This enables a new category of self-certifying applications that can be replicated by any number of peers in an open network without relying on blockchains, waiting for consensus, or imposing transaction fees.

This post is a high-level introduction to causal logs by analogy to traditional logs; the next post introduces GossipLog, a general-purpose replicated causal log built on libp2p.

The humble log is the invisible technology at the core of almost every distributed system. Databases use logs to order transactions. Blockchains are a kind of log. Logs-as-in-logging are logs. "Event sourcing" is the fancy system-design word for doing things with logs.

Jay Kreps wrote a great introduction to the understated significance of logs in which he highlights two particular roles:

The two problems a log solves—ordering changes and distributing data—are even more important in distributed data systems. Agreeing upon an ordering for updates (or agreeing to disagree and coping with the side-effects) are among the core design problems for these systems.

The first property is that storing changes (broadly interpreted) in a canonical sequential total order is intrinsically useful: it lets anyone deterministically reduce over the log and derive the exact same final state. The second property is that logs are easy to replicate: since they're append-only, a replica can check for new data using just its latest ID/timestamp.

Really, the log isn't doing anything. It's just an abstraction over the hard part, which is ordering events in the first place. In a classic CRUD app built on a traditional database, events originate as potentially-concurrent POST requests in a multi-threaded HTTP server, and end up committed to the database sequentially. The database's internal write-ahead log turns simultaneous events into linearized ones.

There's only ever been one way of actually doing this: funneling everything through a single thread on a single process on a single machine. This is true even in distributed databases with clusters of replicas. Paxos, Raft, etc. just coordinate to elect a leader who is responsible for processing events. The leader can change, and there's consensus on who the leader is, but every event still has to go through one machine in order to make it into the log.

Blockchains are not actually different in this respect. Only one block proposer can append at a time (and order individual transactions themselves), and the entire network has to artificially rate-limit blocks to accommodate this. This results in low throughput and non-negligible transaction costs to support the network operators. Decentralizing a log - running on an open network with Byzantine fault tolerance - can only be done with serious sacrifices.

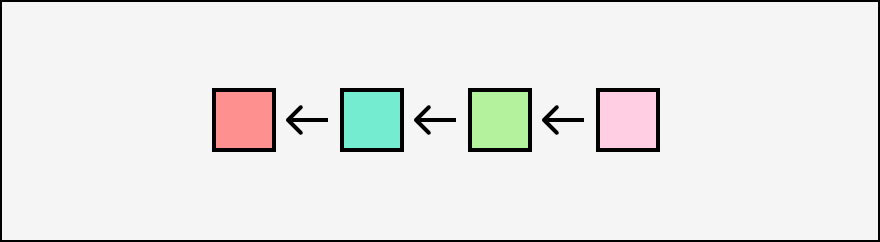

Causal logs relax the total ordering constraint, allowing events with multiple parents instead of exactly one.

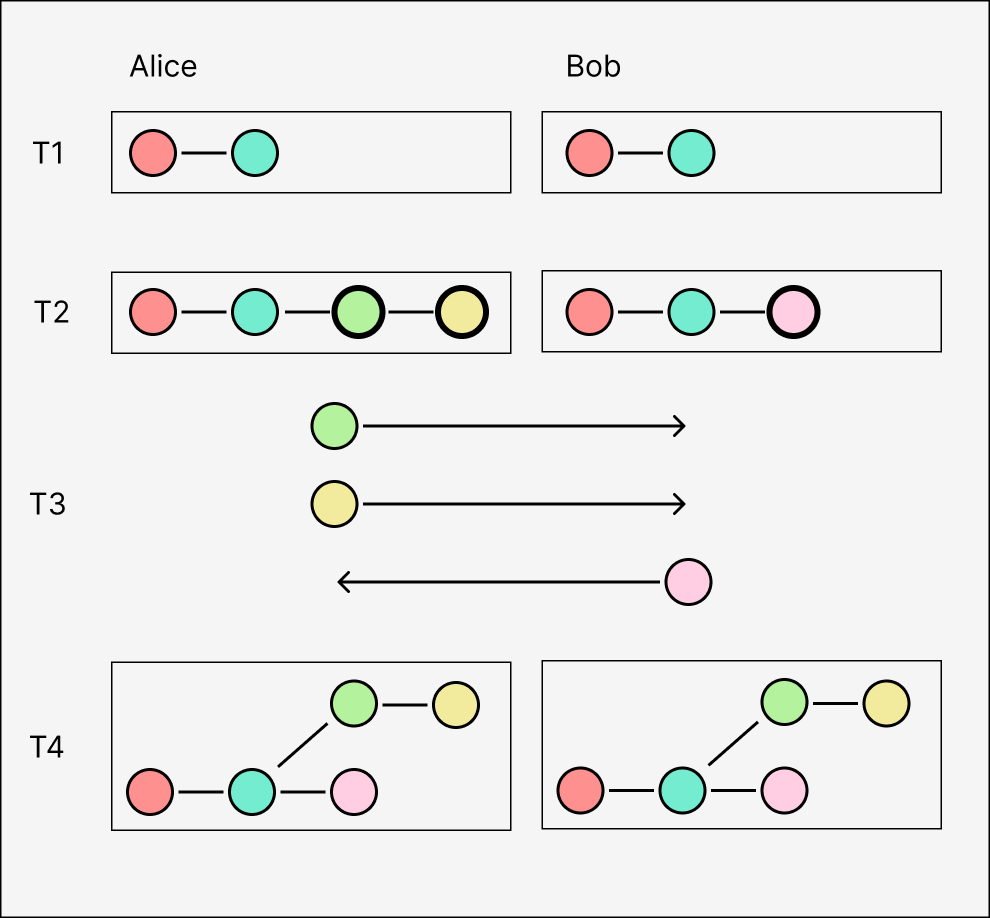

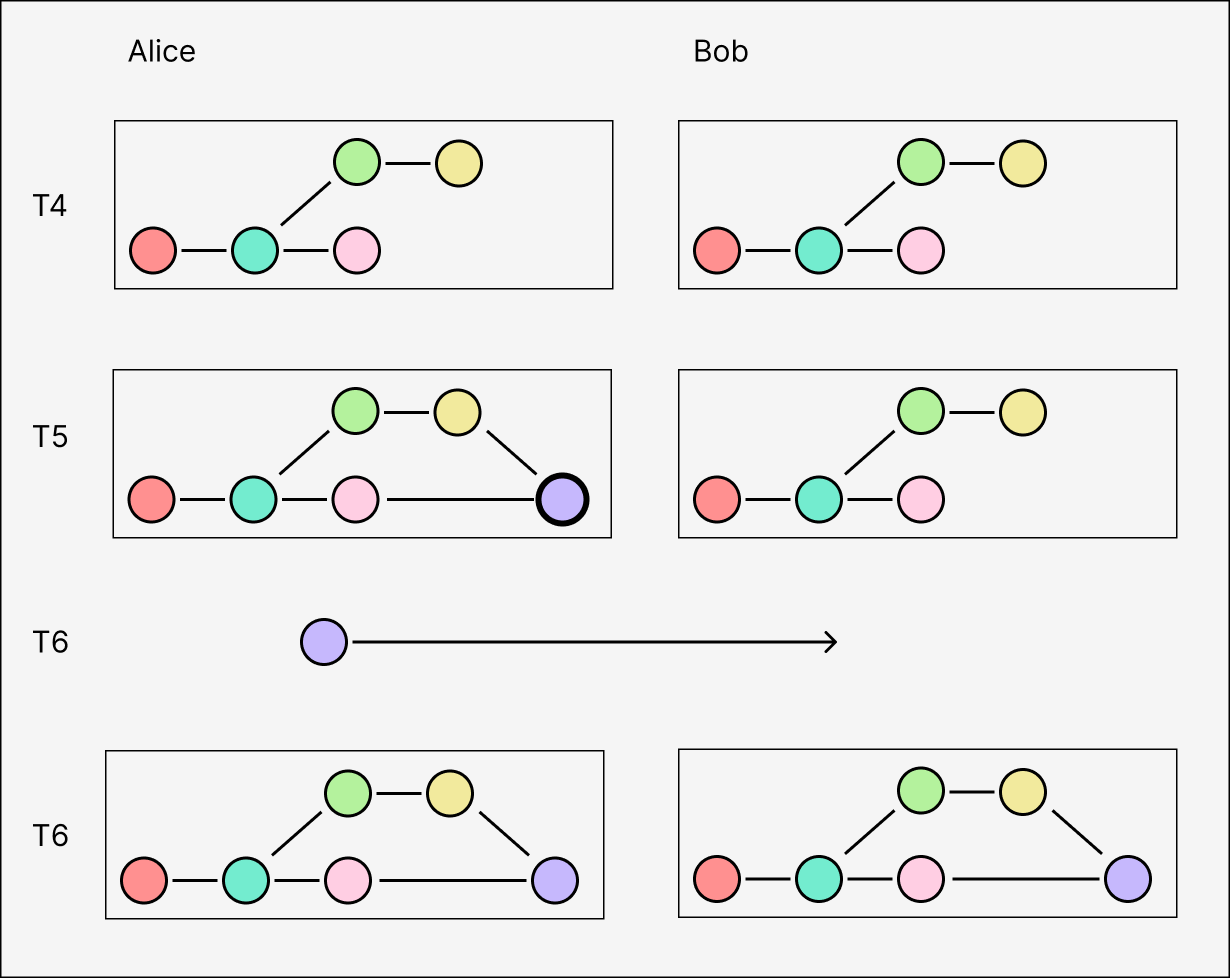

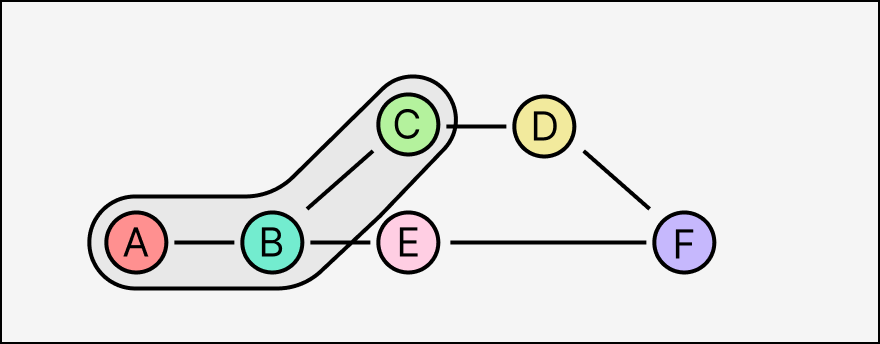

Causal logs are truly multi-writer. Any number of peers can replicate the log, and they can each directly write to their local replica at any time without going through an individual leader or transaction mempool. Here, Alice and Bob start with the same state, write to their logs separately, and send each other the new events afterwards.

(For clarity, we'll use "append" to refer to the initial creation of a new event by a particular replica, and "insert" for the ingestion of an existing event received from another replica.)

This means concurrent events result in parallel branches. Branches might be arbitrarily long (e.g. in the case of a network partition or an offline node) and there may be arbitrarily many of them at once, but divergent replicas can always sync their logs once they reconnect. "Syncing" means exchanging missing events, which we will examine in more detail later.

A causal log superficially resembles a Git repository. Branches in the log can be "merged" by appending an event with multiple branch heads as parents, similar to a merge commit. But an important difference is that in Git, merge commits are semantically meaningful: they represent a deliberate action taken by the programmer to explicitly resolve conflicts. For causal logs, merging isn't a separate kind of event, and doesn't relate to the contents of the different branches. A replica always merges all of its concurrent branches every time it appends.

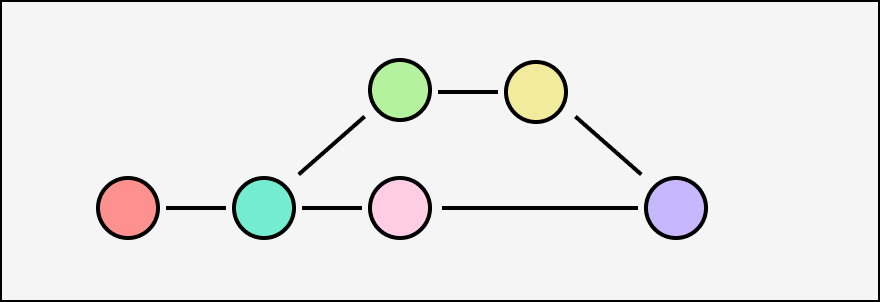

Causal logs only use the graph structure to record the partial order in which events are created relative to each other. One consequence of this is that an event's set of transitive ancestors are exactly the state of its origin replica's log at the time it was appended. Here, everyone can tell by looking at the graph that when Alice created event C, she had only received A and B, not E (or D or F).

Traditional logs operate with useful guarantee that entries are applied in exactly the same order for all replicas. This guarantee is the basis for the consistency of distributed databases. If two transactions write conflicting values to the same record, everybody needs to agree on which to apply first.

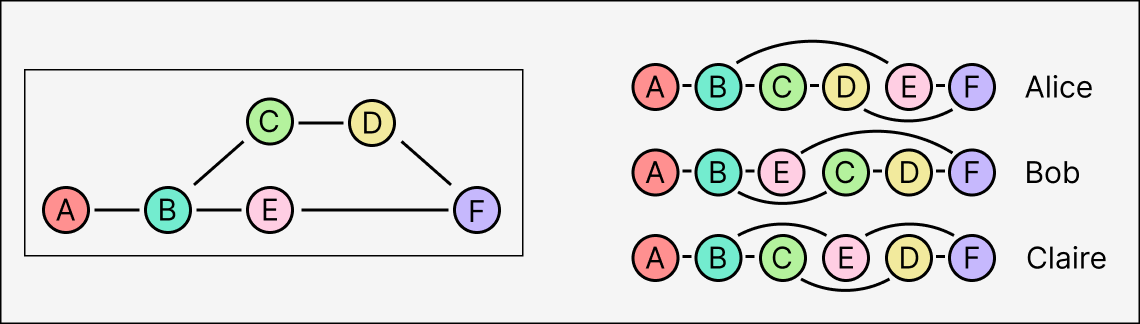

Causal logs have a weaker guarantee: entries are applied in causal order. Parents are always applied before their children, but different replicas might receive and apply different concurrent branches in a different order. In the example from earlier, Alice would apply A-B-C-D-E-F, Bob would apply A-B-E-C-D-F, and a third replica Claire might even apply A-B-C-E-D-F.

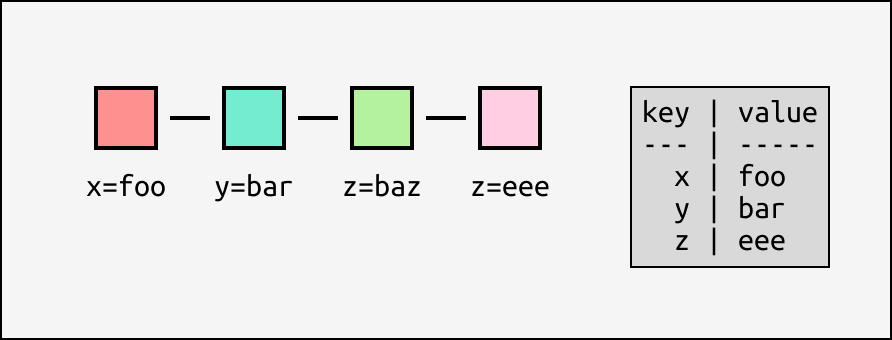

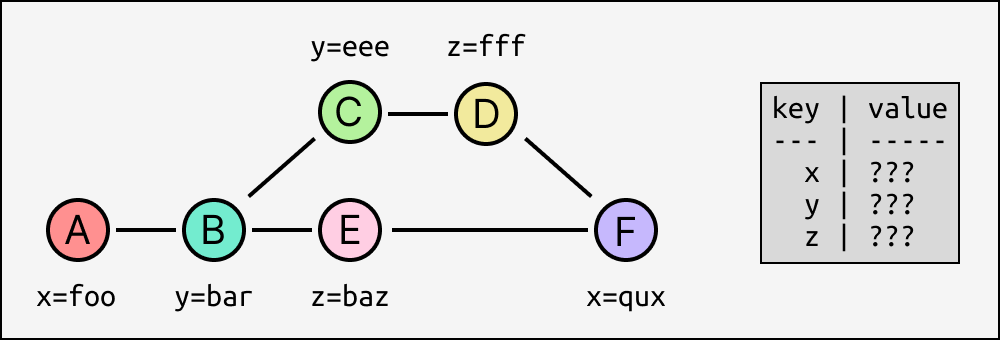

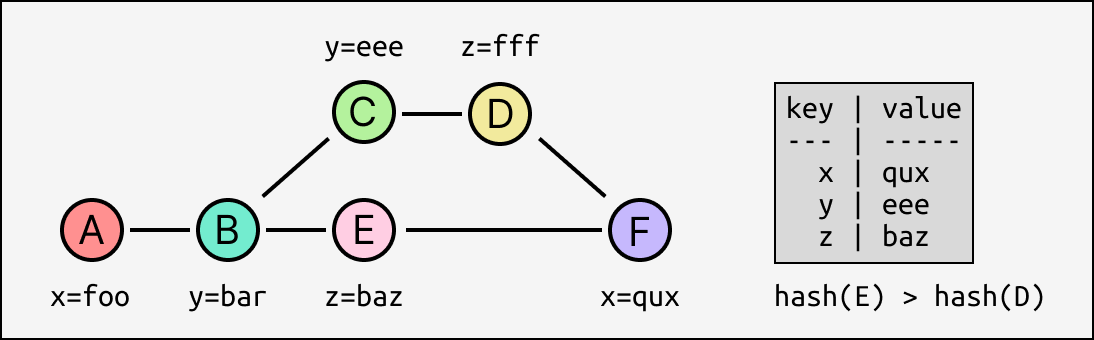

Let's look at a toy example again. What should the state of everyone's key/value store be after applying these entries?

It's easy enough to say that x=qux from F should overwrite x=foo from A, because A is in F's set of transitive ancestors (there's a path from A to F), so whoever appended F had already applied A and thus we can assume they "intended" to overwrite it. Same goes for y=eee taking precedence over y=bar. But we also have two effects z=baz and z=fff that are mutually concurrent - neither directly precedes the other. How do we pick one to win?

There isn't a specific right answer. If Alice and Bob were writing to a traditional database at the same time they'd expect it to just pick an order arbitrarily; that's just what happens. The only thing we can do here is establish a deterministic way of choosing between concurrent writes. The simplest is to compare the hashes of the events and take the higher one - now everyone converges to the same state, regardless of the topological order applied!

In practice, this involves tracking enough additional state to efficiently evaluate effect precedence: a way to easily tell if two events are ancestors or not, adding a version to each key/value entry to store source event hashes, and a table of "tombstones" to record deletes.

What we've derived in the last example is a last-writer-wins register (LWW), one of the basic types of CRDTs. In fact, the generalized process of reducing over partially-ordered changes to get a deterministic value is the literal definition of an operation-based CRDT.

CRDTs are generally presented as a data structure and an operation: apply for operation-based CRDTs, or merge for state-based CRDTs. This emphasizes the safety guarantee, called strict eventual consistency, that peers will converge to the same state after receiving the same set of updates. But how do peers actually broadcast CRDT operations? How do they know if they missed any? The commutative data structures are just one part of a replicated system, and most real-world CRDT frameworks like automerge implement some type of internal causal log to help order and sync operations between replicas.

But a causal log can be also be viewed as a concurrent generalization of a blockchain. Isolating the causal log as a foundational abstraction has some practical benefits:

- a single log can replicate operations on many different CRDTs

- a single log can handle authentication and access control for an entire application

- handle encrypted/private data as log "middleware"

- handle timestamping / blockhashes as log middleware

- enable server replication / cloud backup without access to decryption keys

Most significantly, it allows us to adapt existing CRDTs to open/public peer-to-peer environments. The only constraint is that the log entries must be self-certifying in addition to commutative. A single decentralized causal log implementation can abstract away the hard parts like networking and syncing, and serve as a general-purpose foundation for making automatically-decentralized applications that anyone replicate and interact with.

We will explore our replicated log implementation and its reliable causal broadcast protocol in more detail in the next post.

Further reading: