The Orientation Game

Joel Gustafson / Posts / 2025-10-29

In 1967, Italo Calvino gave a remarkably prescient lecture called Cybernetics and Ghosts, in which he indulged in a little speculation about whether a computer could ever write great literature.

Calvino’s position in doing so is fairly unique: a great author nearing the end of his career, deeply engaged with the world of his time, and fascinated by the birth of computing. He name-drops von Neumann, Shannon, Kolmogorov, and Norbert Weiner.

So what does he say? Surely there is something essential, human, ensouled about great works of art that can never be replicated by machines?

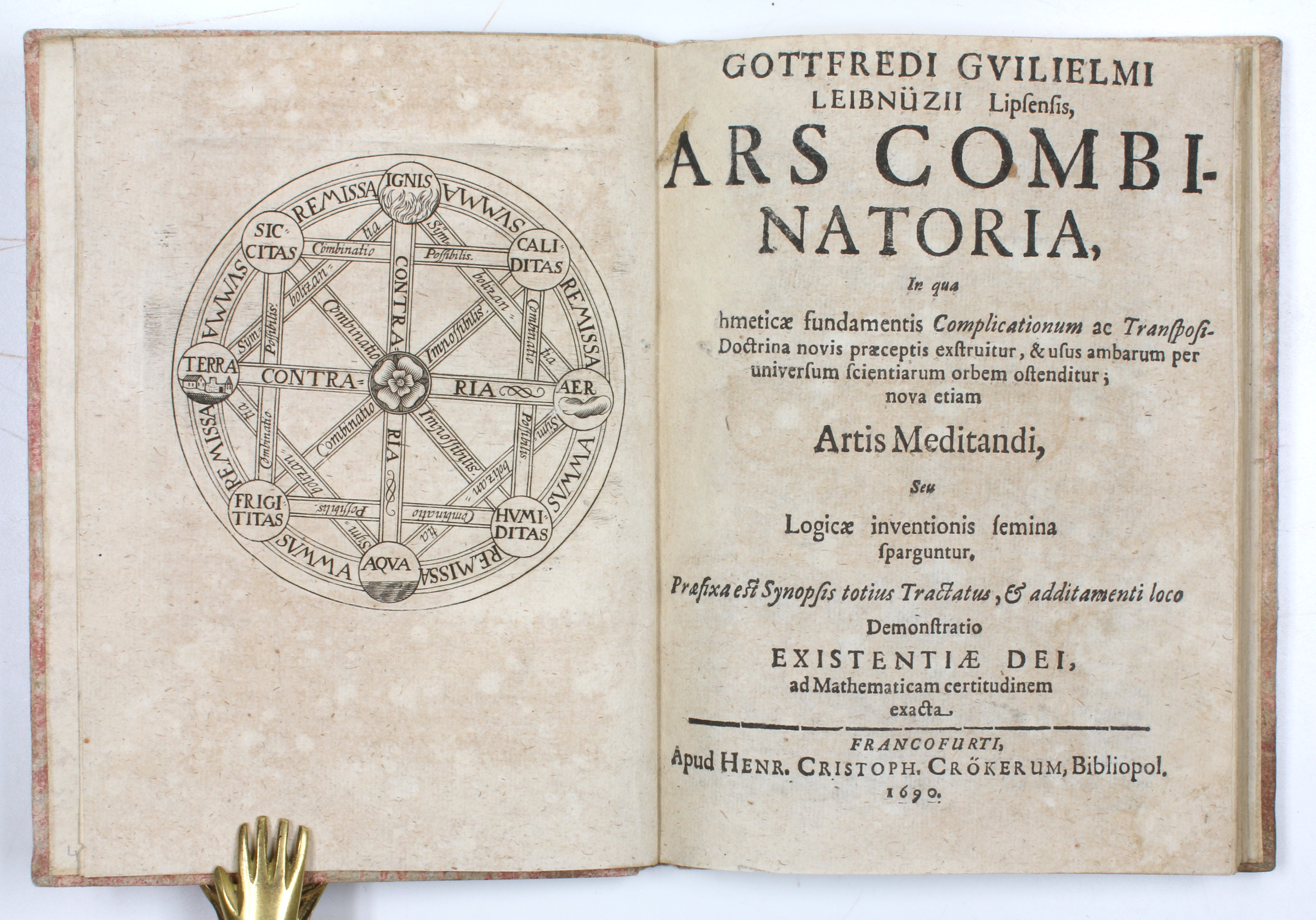

Well... no. Calvino notes some parallels among past and current attempts at formal analysis of language — Chomsky grammars, structural linguistics, a Catalan monk’s designs for the mechanical production of divine truths, early developments in machine learning — and projects that eventually, language itself will give way, and analytical methods will give us a comprehensive grasp of the whole affair. One day, we will have computers that can produce top-notch work within any genre, or create new genres wholesale. Moreover, Calvino admits that, as an writer, he essentially sees his own work as the simple permutation of tokens in a narrative grammar, and looks forward to the day that cranking out stories can be left to the machines.

But what about the soul!? What about experience, subjectivity, qualia? What about the special magic sauce that makes art art?

... I have always known, more or less obscurely, that things stood this way, not the way they were commonly said to stand. Various aesthetic theories maintained that poetry was a matter of inspiration descending from I know not what lofty place, or welling up from I know not what great depths, or else pure intuition, or an otherwise not identified moment in the life of the spirit, or the Voice of the Times with which the Spirit of the World chooses to speak to the poet, or a reflection of social structures that by means of some unknown optical phenomenon is projected on the page, or a direct grasp on the psychology of the depths that enables us to ladle out images of the unconscious, both individual and collective; or at any rate something intuitive, immediate, authentic, and all-embracing that springs up who knows how, something equivalent and homologous to something else, and symbolic of it.

But in these theories there always remained a void that no one knew how to fill, a zone of darkness between cause and effect: how does one arrive at the written page? By what route is the soul or history or society or the subconscious transformed into a series of black lines on a white page? Even the most outstanding theories of aesthetics were silent on this point. I felt like someone who, due to some misunderstanding, finds himself among people who are discussing business that is no business of his. Literature as I knew it was a constant series of attempts to make one word stay put after another by following certain definite rules; or, more often, rules that were neither definite nor definable, but that might be extracted from a series of examples, or rules made up for the occasion — that is to say, derived from the rules followed by other writers.

He continues with an eerily prescient comment about how easy it will be for these future writing machines to roleplay any number of characters, even foreshadowing nostalgebrist’s observations about the void at the bottom of LLM’s RLHF’d identities.

And in these operations the person “I”, whether explicit or implicit, splits into a number of different figures: into an “I” who is writing and an “I” who is written, into an empirical “I” who looks over the shoulder of the “I” who is writing and into a mythical “I” who serves as a model for the “I” who is written. The “I” of the author is dissolved in the writing. The so-called personality of the writer exists within the very act of writing: it is the product and the instrument of the writing process. A writing machine that has been fed an instruction appropriate to the case could also devise an exact and unmistakable “personality” of an author, or else it could be adjusted in such a way as to evolve or change “personality” with each work it composes.

So then what? Is it all over for us?

Once we have dismantled and reassembled the process of literary composition, the decisive moment of literary life will be that of reading. In this sense, even though entrusted to machines, literature will continue to be a “place” of privilege within the human consciousness, a way of exercising the potentialities contained in the system of signs belonging to all societies at all times. The work will continue to be born, to be judged, to be destroyed or constantly renewed on contact with the eye of the reader. What will vanish is the figure of the author... The rite we are celebrating at this moment would be absurd if we were unable to give it the sense of a funeral service, seeing the author off to the Nether Regions and celebrating the constant resurrection of the work of literature.

RIP writing.

That “the decisive moment of literary life will be that of reading” is our first hint of redemption. Calvino recites something of a eulogy for the author, which may sound familiar. His friend Roland Barthes published the essay “The Death of the Author” that same year, 1967, with roughly the same thesis: that meaning is not intrinsic in a text, but rather created through the act of interpretation.

Still, I initially struggled to interpret the full picture that Calvino describes in the second half of Cybernetics and Ghosts. He first says that good writing does — actually — have a kind of hidden depth, in the form of things not said, taboos, or subconscious echos of the past. Some stories can elicit reactions deeper than their literal meaning, pointing to things familiar or repressed but inexpressible within the grammar. But isn’t this just another ad-hoc version of “soul”? How could it differ from any of the other nuances of writing that LLMs effortlessly absorb and reproduce?

Calvino then takes a sharp detour into topology. He begins quoting at length from another essay by German poet Hans Magnus Enzensberger entitled “Topological Structures in Modern Literature”, which applied some casual topological analysis to the variety of ways that recursive, self-referential, or story-within-a-story narratives can be structured. Enzensberger picks a few examples from French theater and German folklore; if written today, he might compare Groundhog Day and Primer.

Enzensberger is ultimately interested in why these constructions, which he collectively names “labyrinths”, are appealing to writers. What is accomplished by leading your characters through a labyrinth? What do we learn by watching them fumble about? In his essay, Enzensberger observes among his examples an underlying ludic theme: the protagonists are asked to play the game, unravel the mystery, solve the labyrinth. This doesn’t mean they’re happy about it, it just means they answered the call; they are game.

Furthermore, a labyrinth is a particular type of game. Enzensberger writes:

What distinguishes such games from all others... is not only their spatial character, but the fact that they force the player to deal with space and to know how to move in it. That’s why I want to mention orientation games... For orientation what matters primarily are not geometric relationships, but topological relationships.

...

Every orientation presupposes disorientation. Only those who have experienced being lost can free themselves from it. That’s why orientation games are, at the same time, disorientation games. In this lies their charm and their danger... The labyrinth is made so that whoever enters it gets lost, so they wander. But at the same time it implies a call to the visitor to reproduce the plan according to which it is built, and thus resolve the confusion. If they succeed, they will have destroyed the labyrinth: for whoever has unraveled it, there is no longer a labyrinth.

The stage for these “orientation games” is the boundary between confusion and comprehension. What is compelling about stories with avant-garde narrative structure is not the complexity as such, but rather seeing how the characters learn to navigate a strange world, grapple with broken logic, push forward through limited visibility, and ultimately reach a moment of enlightenment.

Calvino summarizes:

... [Enzensberger] evokes the image of a world in which it is easy to lose oneself, to get disoriented - a world in which the effort of regaining one’s orientation acquires a particular value, almost that of a training for survival.

What should “orientation” be taken to mean? In my view, it is simply one’s understanding of the world, framed in a way to distinguish it from bare facts. Orientation encompasses our entire worldview, common sense, understanding of ourselves, each other, our attitudes, values, and purpose. These are not freely chosen beliefs of the individual, nor arbitrary products of cultural forces, but a gigantic relational complex that anchors us to the real world. Even science, as Paul Feyerabend would argue, is fundamentally anarchic, an open-ended struggle to align imperfect models with incomplete information.

Orientation mediates our experiences, so it is difficult to even notice, much less change. Similarly, the keys to the various labyrinths in Enzensberger’s stories cannot be represented as simple facts within their respective worlds. Such an embedding would be topologically impossible. Instead, the characters must play the orientation game, feeling their way forward in the dark. As Calvino says, this requires a special kind of effort, different from normal strength or skills.

This, at last, is the synthesis of all of our threads. This particular “effort of regaining one’s orientation” is the same critical effort exerted by the reader to interpret literature (all literature, not just speaking of labyrinths now). The goal of reading is not to receive information, nor simply to “feel” one way or another, but to wrestle with ways of seeing the world that we don’t quite understand yet. Reading is strength training for labyrinth-solving.

From this perspective, Calvino’s comments about the collective subconscious seem less woo.

Literature follows paths that flank and cross the barriers of prohibition, that lead to saying what could not be said, to an invention that is always a reinvention of words and stories that have been banished from the individual or collective memory...

The unconscious is the ocean of the unsayable, of what has been expelled from the land of language, removed as a result of ancient prohibitions. The unconscious speaks - in dreams, in verbal slips, in sudden associations - with borrowed words, stolen symbols, linguistic contraband, until literature redeems these territories and annexes them to the language of the waking world.

The power of modern literature lies in its willingness to give a voice to what has remained unexpressed in the social or individual unconscious: this is the gauntlet it throws down time and again. The more enlightened our houses are, the more their walls ooze ghosts. Dreams of progress and reason are haunted by nightmares.

He is not talking about ability or inability of machines to imbue text with ‘ghosts’, but rather describing the big-picture history of how the entire human artifice has been built up over time. We pulled ourselves up by our bootstraps by playing one orientation game after another. At every turn, we are confronted with a strange world with mysterious workings. At first, we fence off the strangeness and confine it to euphemism, myths, ghosts. But eventually, a hero comes along and solves the labyrinth, showing how all the strangeness fits together into a cohesive whole. Then we notice even more strangeness, and so on.

I wonder if Calvino would have been better served by talking about metaphors instead of ‘taboos’. As Lakoff and Johnson observed in Metaphors We Live By, nearly every apparently object-level concept is really a metaphor — once a novel construction or clever analogy, and gradually integrated over time into everyday vocabulary. The meaning of a metaphor is not always immediately apparent. It may need to be “picked up” by observing its use, during which it will sound strange, even spooky. In fact, the most useful metaphors are exactly the ones that reach beyond the existing vocabulary, finally grasping something familiar but nameless.

At any rate, Calvino doesn’t really care about finding a bound on the capabilities of computers. Instead, he’s trying to identify the thing that really matters so that we can all make sure to attend to it after machines start taking over auxiliary things like writing books. What matters is that we continue to engage with the world in a way that advances our collective understanding.

Are we done? Isn’t there still the question: can a machine play the orientation game for us?

Well, the point of the game is to understand things. Even apart from the question of whether an LLM ‘really’ understands the world, we want to understand things for ourselves, and the kind of understanding we’re talking about is the most difficult kind to acquire: ways of seeing, not sets of facts.

Can a machine help us play the game? Absolutely! Calvino would be first in line to play around with LLMs as “a way of exercising the potentialities contained in the system of signs”. But now with this framing, it’s clear that it’s still up to us to develop the right ludic attitude, and that LLMs have just as much potential to inhibit orientation as they have to assist with it.

Enzensberger’s essay concludes with a warning that labyrinth stories must strike a delicate balance to be effective. Narratives that are overly convoluted devolve into nihilism, “and literature turns into a means of demonstrating that the world is essentially impenetrable, that any communication is impossible. The labyrinth thus ceases to be a challenge to human intelligence and establishes itself as a facsimile of the world and of society.”

Calvino continues in the same vein:

Enzensberger’s thesis can be applied to everything in literature and culture that today — after von Neumann — we see as a combinatorial mathematical game. The game can work as a challenge to understand the world or as a dissuasion from understanding it. Literature can work in a critical vein or to confirm things as they are and as we know them to be. The boundary is not always clearly marked, and I would say that on this score the spirit in which one reads is decisive: it is up to the reader to see to it that literature exerts its critical force, and this can occur independently of the author’s intentions.

The evil twin of an orientation game is a word game. Word games are self-contained, untethered, “a facsimile of the world and of society”. Orientation games bring us into alignment with the world; word games cut us further adrift.

LLMs pose a particular danger because of their tenuous alignment with the real world, making it harder tell which kind of game you're really playing. Furthermore, LLMs themselves exhibit the same sort of slippery topological convolution, a resistance to easy categorization with our existing vocabulary. We must push beyond simplistic takes to regain our footing in this strange new world, through humility, critical thinking, and a willingness to play the orientation game.